Bailey Piotrowski ’19 is spending the summer searching for planets in distant solar systems, quadrillions of miles from Earth. Abigail Pamenter ’19 and Walker Kelly ’19 are analyzing skull fragments of 130,000-year-old fossils from Neandertal adults and children. Hanna Hertzler ’21 and Keira Congo ’20 are sifting through samples of sand they collected on a Cape Cod beach, looking for tiny bits of plastic that are threatening the coastal environment.

These Vassar students and more than two dozen others are working with Vassar faculty under the auspices of Vassar’s Undergraduate Research Summer Institute (URSI). The projects are enhancing their study of science well beyond the work they’ve done in the classroom.

Echoing the sentiments of many of his URSI colleagues, Kelly said the project he is tackling this summer has given him new insights into how scientific research is conducted. “I’ve never had the opportunity before to devote this much time to one project and to be given the freedom to develop methods for solving problems,” he said. “Abi (Pamenter) and I are fully immersed in this work. Sometimes at dinner, we’ll still be discussing a breakthrough we made earlier in the day.”

This summer’s 28 URSI projects include research in anthropology, astronomy, physics, chemistry, cognitive science, computer science, earth science, mathematics, and psychological science. The students will present their findings at Vassar’s annual URSI Symposium Sept. 26 at 3 p.m. in the Villard Room. The keynote speaker will be Deborah Estrin, Associate Dean and Professor of Computer Science at Cornell Tech in New York City. Following are brief reports on three URSI projects.

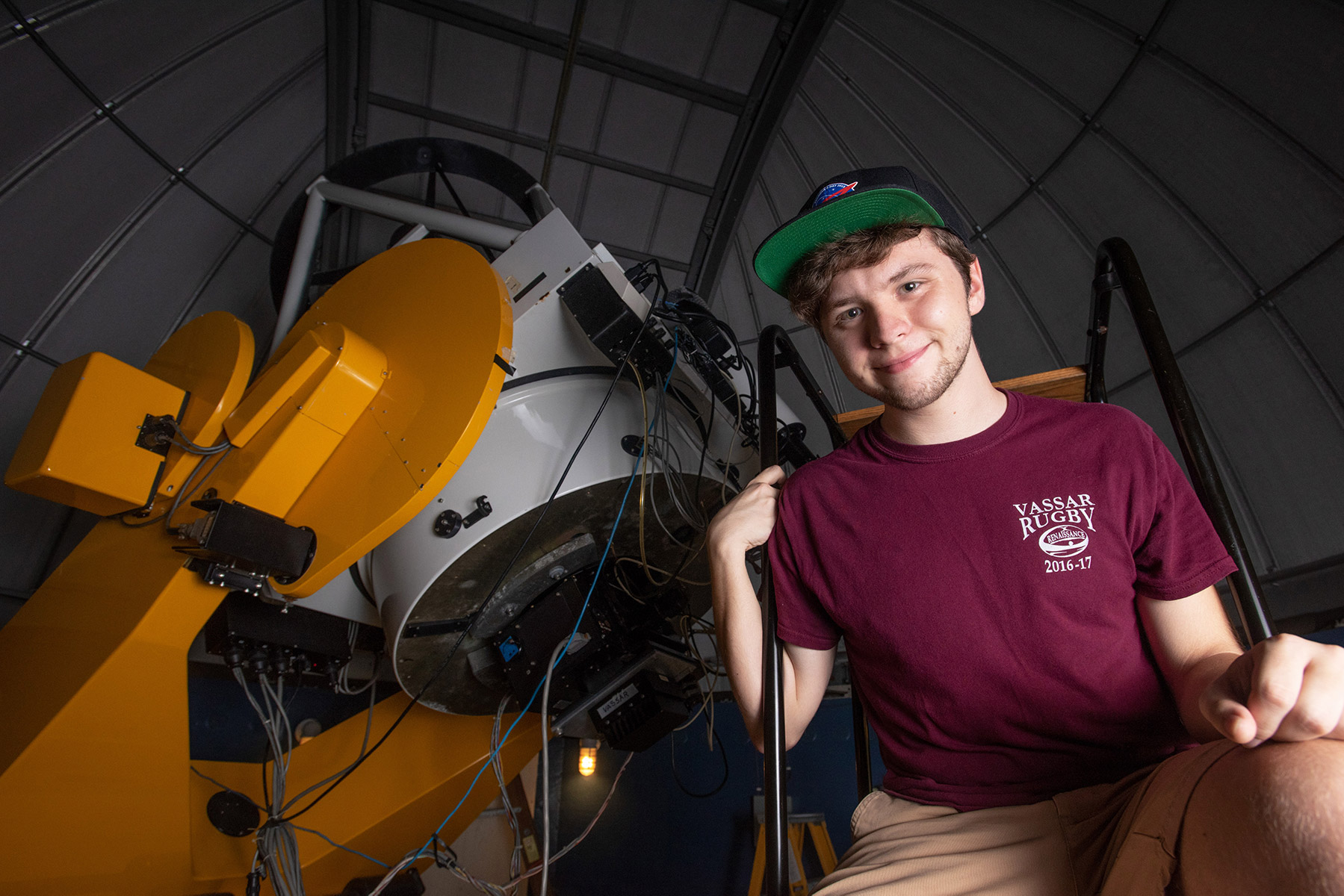

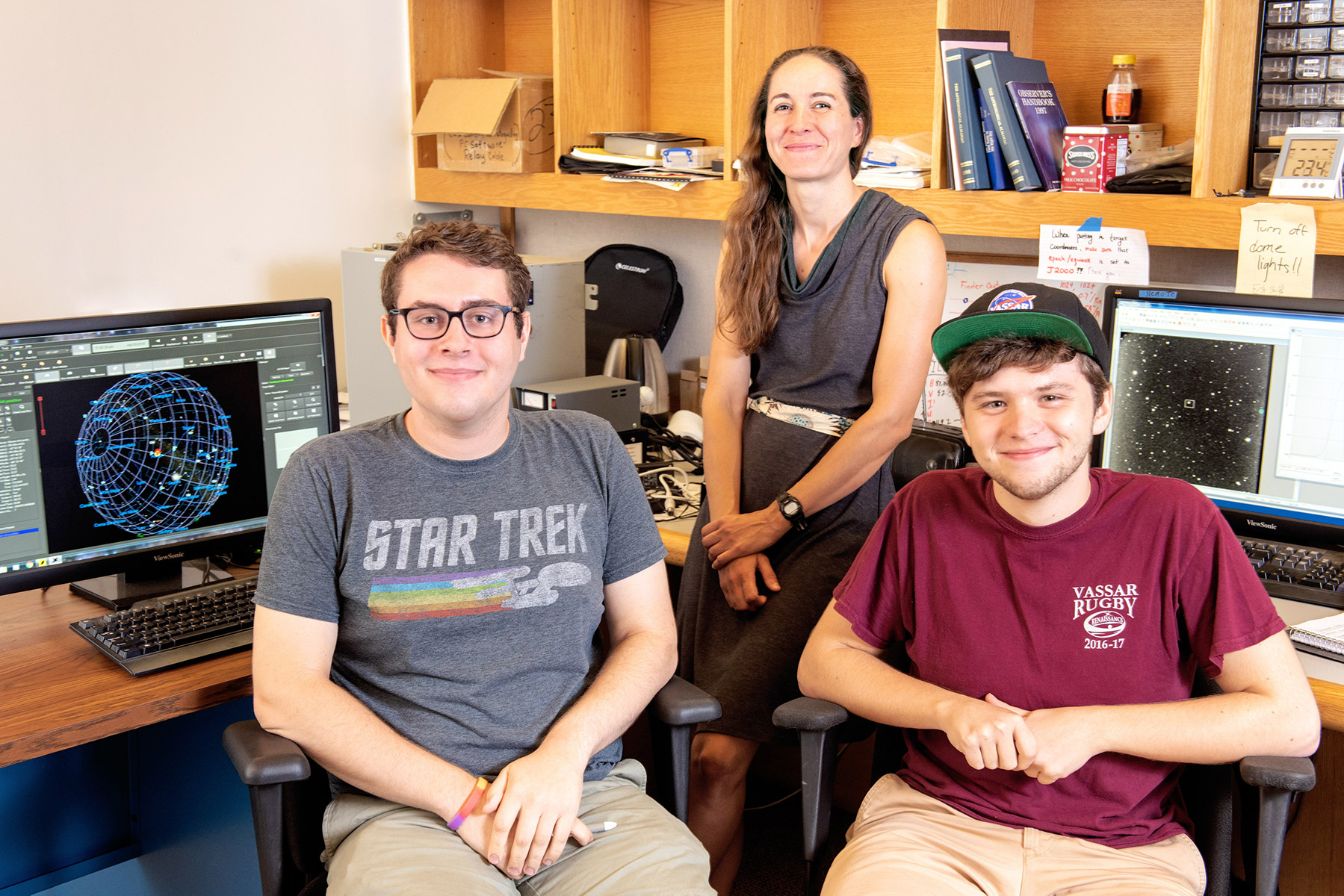

Searching for exoplanets: Assistant Prof. of Astronomy Colette Salyk, Bailey Piotrowski ’19 (Vassar) and Aidan Pidgeon ’19 (Dickinson College)

Finding evidence of planets orbiting stars far beyond our own solar system is anything but a singular task. Throughout the United States and several countries around the world, professional and amateur astronomers are scanning the skies and trading information generated by images gathered by two telescopes located in Arizona and South Africa. The worldwide search is being conducted under the auspices of the whimsically named Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescopes (KELT).

Astronomers participating in the KELT program are looking for stars whose brightness dips for short intervals when planets pass in front of them, Salyk explained. Some such stars are visible through Vassar’s telescope, so Piotrowski and Pidgeon are examining those suspected of having planets orbiting them. Most of the planets detected by Vassar’s telescopes are approximately the size of Jupiter, she said.

During their research, Piotrowski and Pidgeon observed an exoplanet known as KELT 8 pass in front of its parent star. Piotorwski, a physics and astronomy double major from Queens, NY, said it was exciting to be part of a large team of astronomers who are breaking new ground. “Before I began this project, I thought this kind of work was only something big telescopes from NASA could do,” he said. “It’s been empowering to see how much we can contribute—gathering the data and analyzing it and reporting on it.”

Pidgeon, whose participation is being funded through the National Science Foundation’s Research Experience for Undergraduates program, agreed. “I think at the start of the summer, we tended to undersell ourselves,” he said. “But we’re making real contributions to science.”

The students presented some of their findings at a conference of the Astronomical Society of New York July 11–13 at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan.

Salyk said she felt fortunate to be working with two gifted, young astronomers. “I feel lucky to have them,” she said. “I knew Bailey had some expertise from his job helping out at the observatory, and Aidan came in with some knowledge about our techniques because Dickinson’s telescope is similar to ours.”

Salyk said she was proud of what she and her students had accomplished during the summer. “It’s cool to think, ‘Yes, we are actually watching planets go past stars,’” she said. “Detecting planets orbiting other stars was first achieved in 1995, so it’s really a brand new chapter of astronomy.”

Rebuilding Neandertals from fossil fragments: Assistant Prof. of Anthropology Zachary Cofran, Abigail Pamenter ’19 and Walker Kelly ’19

One of the best ways to figure out what our ancient ancestors looked like is to collect some fossils of their bones and try to reconstruct them. That’s what Prof. Cofran and his students are doing this summer, analyzing replicas of fossils of several hundred Neandertal bone fragments that were discovered in Croatia in 1899.

Cofran traveled to Croatia’s natural history museum in Zagreb last year, made 3D models of the fossils and brought them back to his lab. For their URSI project, Pamenter and Kelly are tasked with figuring out exactly which parts of the skull they belong to, how old the Neandertals might have been when they died and whether any of the fragments could go together.

“We’re sorting the bones by size and thickness for the first time this summer,” Cofran said, adding he had selected Pamenter for the project because she had some working knowledge of software that is used to make digital images of the fossils.

Kelly, a psychological science major and anthropology minor from Galesburg, IL, said he had to learn “five or six different software packages” to conduct the study, but he was soon able to gather usable data. “We’re getting pretty good at plotting points on the skull where the bones come from,” he said. “We perfected some data collection methods that we think other researchers can use in the future.”

While the students are wrapping up their analysis and awaiting results, they plan to present a paper on their findings at a conference of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists in Cleveland next spring. Cofran will discuss the work he did with the students at the annual meeting of the European Society for the Study of Human Evolution this fall in Portugal.

Pamenter, a biology major from Springfield, IL, said working on the project this summer had inspired her to consider a career in anthropology. “I’ve done some independent research before, but nothing this intense,” she said. “It’s cool finding things out that nobody else knows.”

Cofran says his students had definitely taught him things he didn’t know about various software programs. “It’s been fun to watch them learn as they work together,” he said. “There have been times when we have different ideas about where a bone fragment may have come from, and when we consult our guide, they’re right and I’m wrong.’ That’s been rewarding, to see they have gained so much expertise that they beat me at a bone quiz.”

Investigating microplastics in coastal sands: Prof. of Earth Science Jill Schneiderman, Hanna Hertzler ’21 and Keira Congo ’20

Children’s toys, trash bags—even some cosmetics—have something in common. They’re made out of plastic, and when they’re discarded they can cause serious harm to birds and aquatic life. Recently, scientists have begun to study the effects of these so-called microplastics that contaminate terrestrial sand and coastal sand dunes.

This summer, Prof. Schneiderman and her URSI students joined the study. They traveled to Sandy Neck Beach Park in Cape Cod in May, scooped up some sand and brought it back to Schneiderman’s lab for analysis.

Schneiderman and her students soon determined two things: First, the sand they had collected did contain what appeared to be tiny pieces of plastic in virtually all of their samples. And second, the standard methods of detecting and analyzing these microplastics needed some refinement. Hertzler and Congo used a dye called Nile red to stain the plastics so the tiny particles fluoresced, making them easy to distinguish from the rest of the sample of sand when viewed under a microscope.

In order to separate the plastic from other materials in the sand, previous researchers had used a solution of sodium chloride. Congo, an earth science major from Nairobi, Kenya, said she and Hertzler and Schneiderman followed a suggestion from one of Schneiderman’s previous interns, Greta Nelson ’21, who determined that zinc chloride worked much better than sodium chloride. This method separated the particles of plastic more efficiently, making it easier for Hertzler and Congo to find what they were looking for when they placed their samples under a microscope.

Schneiderman said that because the study of microplastics is so new, she and her students were reading papers on others’ research that had been published as recently as a few months ago. “All of us are really on the ground floor of this study,” she said.

Hertzler, an undeclared major from Trumansburg, NY, said her URSI experience had taught her that science is truly a trial-and-error endeavor. “I’m using the phrase, ‘flying by the seat of our pants’ a lot this summer,” she said. “What we’re doing is so much more fun than the lab projects we do during our class work where you know the supposed outcome. At the behest of Vassar lab technician David Lewis, I recently wrote a procedure for our faculty to follow if they want to conduct lab experiments with their students sometime down the road.”

Schneiderman said she was impressed with the work Congo and Hertzler had done but not surprised. “Keira had been my student in my intro geology course and Hanna was a student in my first-year writing seminar on the Anthropocene,” she said. “Both were outstanding students, responsible, meticulous, and eager learners. What has been so remarkable about working with them is that where I would have wanted to rush to collect data, they were patient and exacting. They wanted to proceed only if they were convinced that the procedure they had developed was as good as it could be, even better than what appeared to be somewhat hasty procedures reported in the scientific literature by other investigators.

“As URSI is a program that is about independent research, I let them run with their ideas and dictate the direction our project would take,” Schneiderman continued. “They have pleased me tremendously in that they are indeed taking the lead on setting our direction and calling the steps by which we would approach the project. I’m confident they will have developed a procedure by which we can study microplastics in the Cape Cod sediments that we can rely on as we move forward.”