Outside the ClassroomOut of Dust, Nascent Planets

Outside the ClassroomOut of Dust, Nascent Planets

Vassar Assistant Professor Colette Salyk is part of a team of astronomers that has gathered new evidence about how planets roughly the size of Earth and Neptune are forming in other parts of the galaxy. The discovery sheds light on how our own solar system was formed.

Salyk was one of 26 astronomers from 24 institutions in eight countries who launched the study in 2016 using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, a cluster of 66 antennas located high in the Andes Mountains in Chile. The astronomers gathered new data on so-called “protoplanetary disks,” which form around stars before the matter eventually morphs into individual planets, moons, asteroids

“This is fascinating because it is the first time that exoplanet statistics, which suggest that ‘super-Earths’ and ‘Neptunes’ are the most common type of planets, coincide with observations of protoplanetary disks,” says the paper's lead author, Feng Long, a doctoral student at the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at Peking University in Beijing, China.

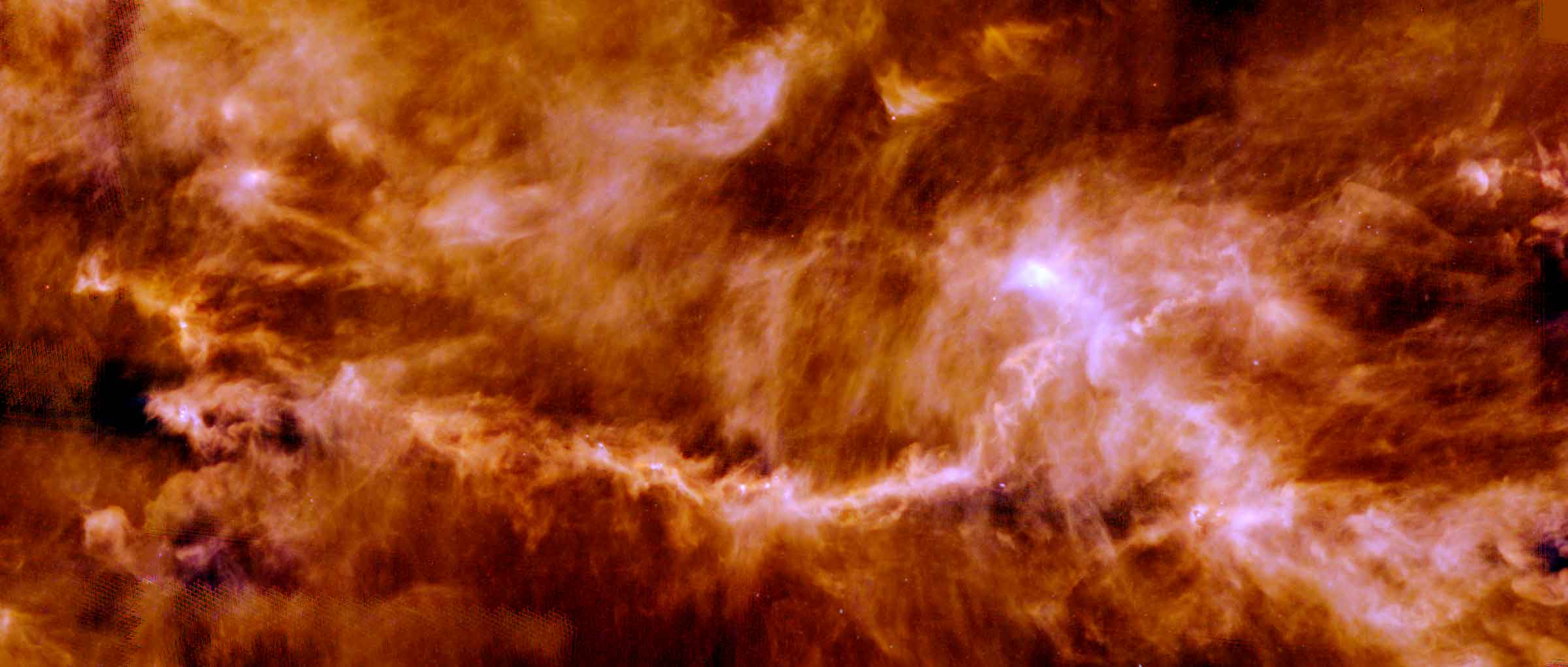

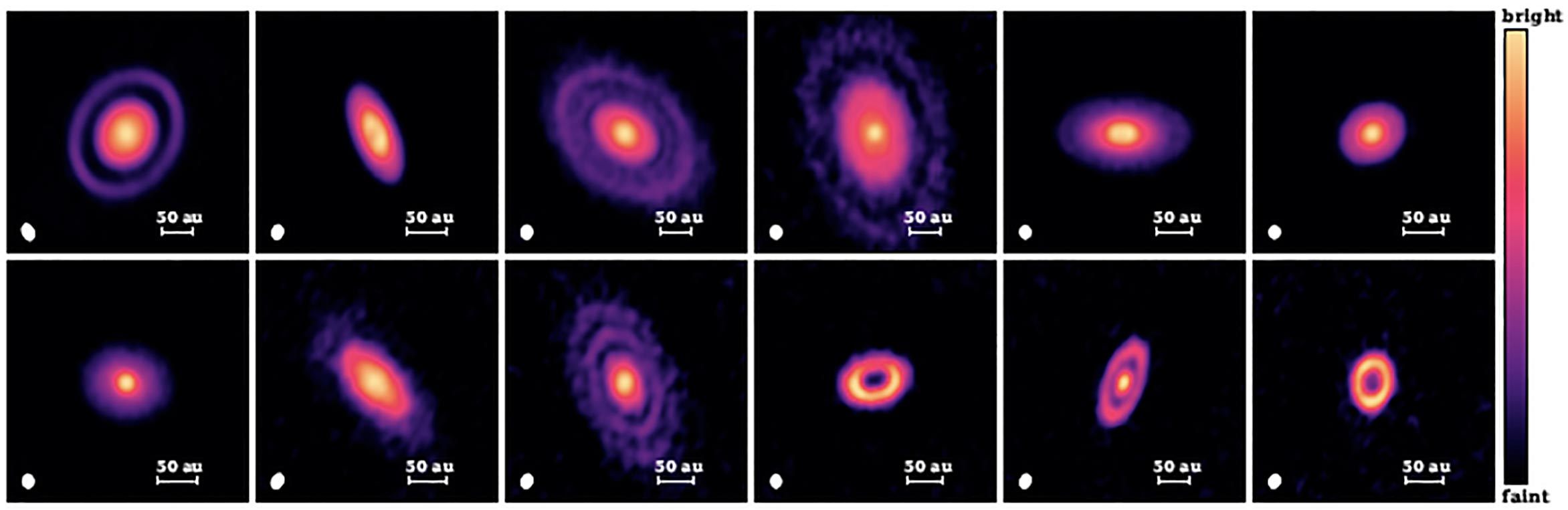

The team performed a survey of young stars in the Taurus star-forming region, a vast cloud of gas and dust located a modest 450 light-years from Earth. When the researchers imaged 32 stars surrounded by protoplanetary disks, they found that 12 of them—40 percent—have rings and gaps, structures that according to the team's measurements and calculations can be best explained by the presence of nascent planets.

Salyk says the data gathered in the study suggest that the signatures of the planets up to 20 times the mass of the Earth may be easier to spot than scientists previously thought. “Prior to these results, we suspected that planets were forming in these disks, and we occasionally caught glimpses of that process,” she says. “But these images show us that there are signs of planet formation everywhere, so long as we have tools sensitive enough to see them.”

Salyk says she and other members of the team will continue their study after they rearrange the Atacama Large Millimeter Array antennas to make them sensitive to even smaller features and to capture other kinds of light. She says she is confident the astronomers will be able to gather new data that shed more light on the formation of planets. “For many years, models of planet formation were much more sophisticated than the blurry images we were able to obtain,” she says. “It has been exciting to be able to use this new tool to finally see the process of planet formation in action, and to let the data surprise us with its beauty and complexity.”