The crisis surrounding COVID-19 has disrupted many lives—especially the lives of our students. But it’s not the first time the campus community has been called to make adjustments in a time of crisis. Find out how the college—and a very special class—adjusted to the realities of WWII.

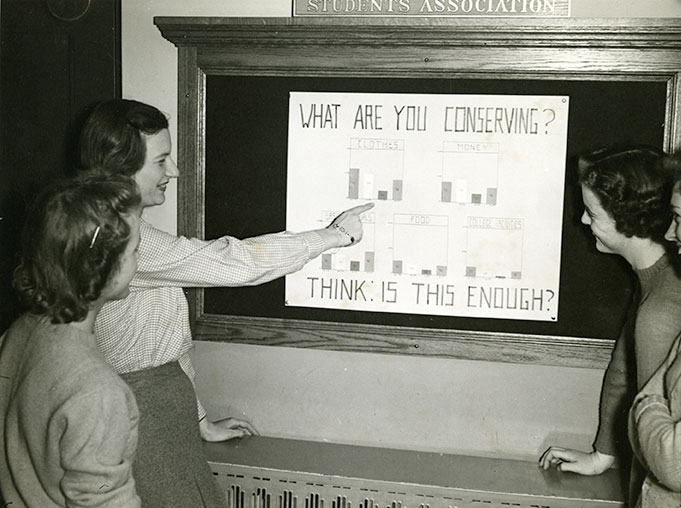

In February 1942, just two months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, a plan was put in motion for Vassar College to help on the homefront. With so many men fighting—there was a significant need for educated women to work as interpreters, nurses, teachers, clerks, and even in the Navy Women’s Reserve (WAVES), the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), and other services— a letter was drafted by the departments of Economics and Sociology calling for emergency action.

“Vassar has often claimed that it is training for leadership, but if in a national emergency we are unwilling to take any initiative, this claim cannot be supported,” the letter read, and continued: “The greatest need will be for trained women who can contribute leadership, imagination, and ingenuity.”

The initiative—which had been bandied about by students, faculty, administrators, trustees, and others since before Winter Break of 1941—was to create an accelerated academic program, graduating educated and qualified women in three years instead of the traditional four.

An ambitious undertaking, it required months of meetings and scores of ideas on how to squeeze so much knowledge into three years. There are hundreds of letters, meeting notes, published articles, and other documents detailing the rigorous process.

Vassar’s Board of Trustees authorized an emergency policy for a three-year course of study at its April 6, 1942, meeting, noted the June 1942 issue of Vassar Alumnae Magazine. This action allowed for the accelerated program, but there were no details on how it would be accomplished.

It took nearly a year of meetings and votes for the program to be implemented on March 5, 1943. The new plan called for three 40-week academic years instead of four 30-week years. Seven seniors who opted into the plan received their degrees at Winter Commencement in December 1943 and three more commencements took place in April, July, and December of 1944—the Class of 1945-4 was the first full class whose members could opt into the accelerated program.

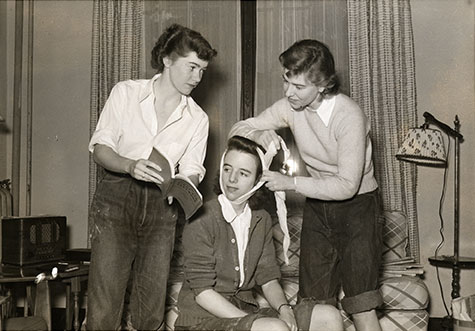

One week after the program was approved, President MacCracken sent a letter to students notifying them of the new academic year model—three terms, two at 15 weeks and a third at 10 weeks. Other changes included cooperative work (cleaning, waiting tables, and other chores) on campus as the college released employees for war work.

Nancy Maguire Pyne ’46 was one of hundreds of graduates who opted into the three-year program.

“We all were very motivated. We were deep into the Second World War,” she says.

In addition to the three terms, students attended classes on Saturdays instead of engaging in the usual weekend activities—visiting sweethearts and attending social functions. Most of the young men were away at war, or helping in the effort on other fronts, Pyne says, so students stayed on campus, forming strong friendships and studying.

“There were no distractions. That’s why I loved it,” she says. “We got a fantastic education because we were totally focused.”

The war ended before Pyne graduated, but she says, “We were prepared to go into this new world that badly needed us.”

There was still much work to be done. The international studies major spent a year at a Zürich university improving her German, a skill later required for her work translating reports in the State Department.

The April 15, 1943, edition of Vassar Alumnae Magazine was entirely devoted to the program. In one article, “Sampling Student Views,” Nancy Crenshaw ’43 noted that students were solidly behind the program and one senior said, “Any plan that will make college cheaper and get students out quicker, well-trained for the war effort, is good.”

The program was so popular that, in its first year, Alumnae House had to be drafted to supply housing to 35 students and some upperclassmen lived cooperatively in Lyman House. The accelerated program was discontinued several years later, with the Class of 1949 its last participant.