For Emma Glickman ’18, the first clues to the story of her family’s ordeal in Nazi-occupied Poland were the tiny bite marks she found on a gold locket her grandmother, Elizabeth Hoffman Glickman, had given her a few years before she died. Since then, the Vassar senior has begun to unravel the mystery further. On April 11, the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day, Glickman gave an hour-long presentation in Rockefeller Hall on what she calls, “The Story of the Bitten Locket: How My Grandmother and Great Grandmother Survived the Holocaust.”

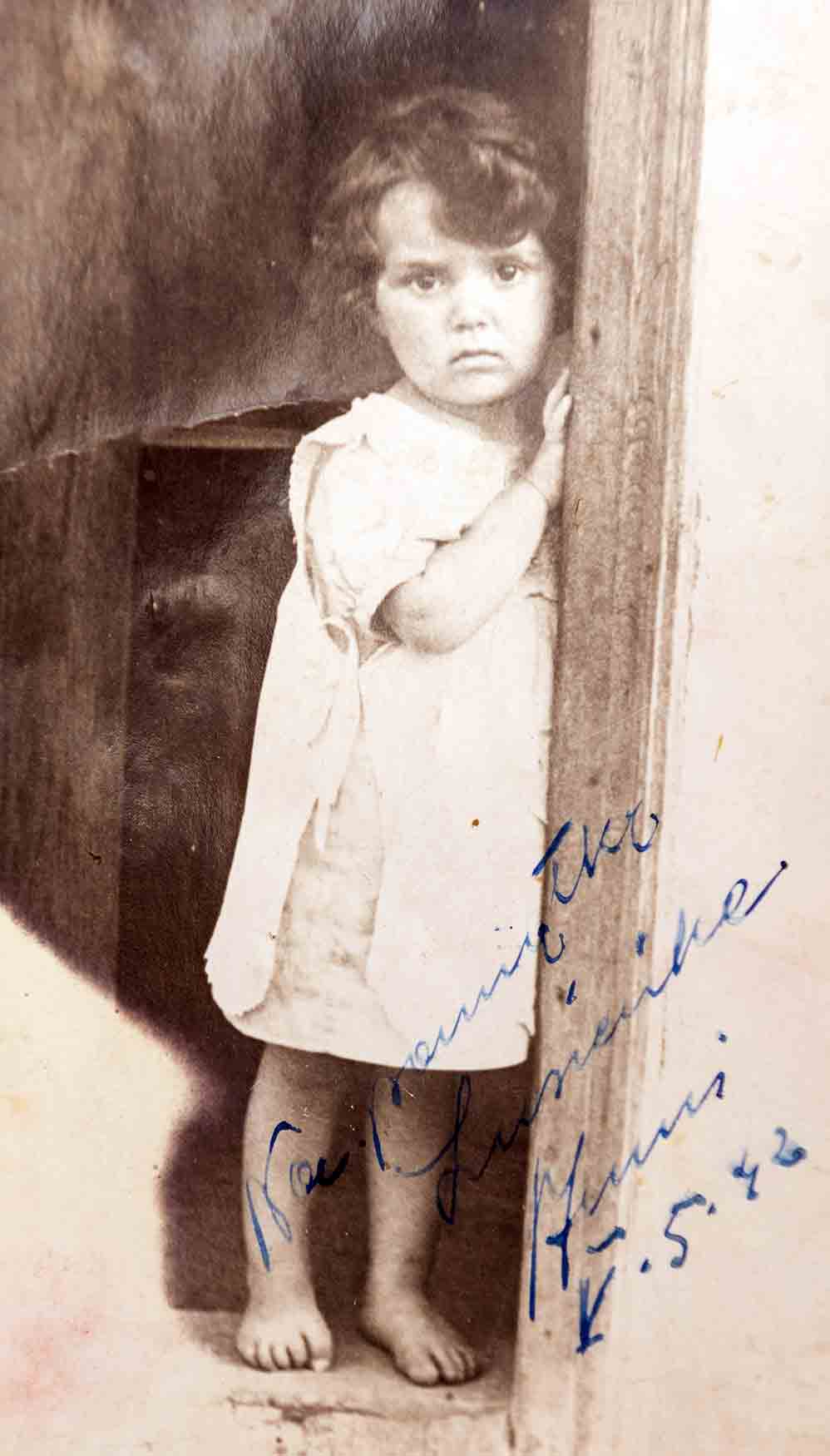

Before she enrolled at Vassar, Glickman had learned that in 1942, when her grandmother was 15 months old, she spent much of her time in a dark closet in the home of a Christian family in rural Poland. The family was harboring the Jewish toddler because she was too young to survive in the woods, where the rest of her family had fled to hide from the Nazis. The girl’s mother, Stefa Trachman, had given her daughter the locket with her photograph inside, and when the toddler feared Gestapo agents who periodically searched Christian homes might find her, she’d bite it to keep from screaming.

Glickman, a Jewish Studies and Psychology double major and Education correlate from Livingston, NJ, chronicled what she knew about her family’s struggles two years ago in an oral history project sponsored by Vassar Refugee Solidarity. “But obviously,” she told the 40 students, faculty, friends and relatives who attended her talk at Rockefeller hall, “I wanted to know more.”

Two emotionally draining trips to Poland helped Glickman unravel much of the story. Accompanied by a Polish interpreter, she traveled to the family’s village of Brzozów. There, in the Jewish cemetery, Glickman found her next significant clue: her great-great-grandmother’s gravestone.

Introducing herself only as an American history student, Glickman went from house to house, seeking information about her family. Mostly, she was met with shrugs and stony silence. But Glickman was heartened when she found a brick along the side of a road in the village that was embossed with a T, proof it had been made at the Trachman brickyard that had been owned by her family.

Frustrated by her failure to find the family that had harbored her grandmother, Glickman and her interpreter decided to ask the editor of a local newspaper to publish a story about Glickman’s quest. A few months later, while she was studying in Denmark during her junior year, Glickman got her first big break: The children of the family that had hidden her grandmother sent her an email saying they had read the newspaper article, and one of the sons, Jan Kielar, said he’d speak to her.

Glickman returned to Poland last summer and Kielar and his sisters showed her photographs of the family posing with her grandmother, and Jan agreed to speak on camera for a documentary that Glickman and a cousin, a documentary filmmaker, had decided to produce. During her talk, Glickman displayed the photographs and showed an eight-minute segment of the film, which she and her cousin hope to finish next year.

Glickman said she intends to continue to hunt for more information about her own family’s struggles and to help others tell their stories. She is hoping to raise enough money to travel to complete the production phase of the documentary film. “We need to keep talking about this because genocides are still happening in the world,” she said.

“I would also like to interview high school students from Brzozów regarding stories they heard from their grandparents or other family members about life for Poles under German occupation,” Glickman added. “Furthermore, I would like to talk to students about the Righteous Gentiles that risked their lives saving my family. My dream is to show this documentary to the community of Brzozów, especially the young generation, and to create a dialogue that has been lost. We must begin engaging in conversations about our past, no matter the horrors that unfold.”