The past year has laid bare in graphic detail the struggles and injustices faced by Black Americans every day. The nation finally began to take notice when it became a literal witness to history through the powerful images captured on cell phones and body cameras that circulated on social and news media. Seeing is believing.

Visible Bodies: Representing Blackness is an illuminating exhibition currently on view at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center that uses the photography made by Black artists to illustrate the critical importance of being seen.

Curator Jessica D. Brier, Deknatel Curatorial Fellow in Photography, points out that photography has always held the powerful promise of making the world more visible, yet it has also been a powerful tool of selective memory and erasure, reinforcing hierarchies between White photographers and Black subjects. A photograph can be as striking for what or whom is excluded from its frame as for what appears within it.

Over the past two decades, police violence against Black Americans has become newly visible through instantaneous circulation of digital photography and video online. Black American writer Elizabeth Alexander recently deemed those who have come of age in this period “The Trayvon Generation,” writing: “Black creativity emerges from long lines of innovative responses to the death and violence that plague our communities.”

Visible Bodies traces this evolution with photographs drawn from the Loeb’s permanent collection. It centers on the tension between visibility and invisibility, inherent to the medium of photography and intrinsic to the Black community, through works by Black American artists. The works in this exhibition exemplify artists’ creative uses of photography to resist colonization, inequity, disenfranchisement, and brutality.

Brier says, “This exhibition was planned during the summer of 2020, as the Black Lives Matter movement was gaining incredible momentum. I saw this moment as an opportunity to promote Black photographers in the Loeb's collection whose work is directly relevant to the communities of Vassar, Poughkeepsie, and beyond.”

Mickalene Thomas, Tamika sur une chaise longue, 2008

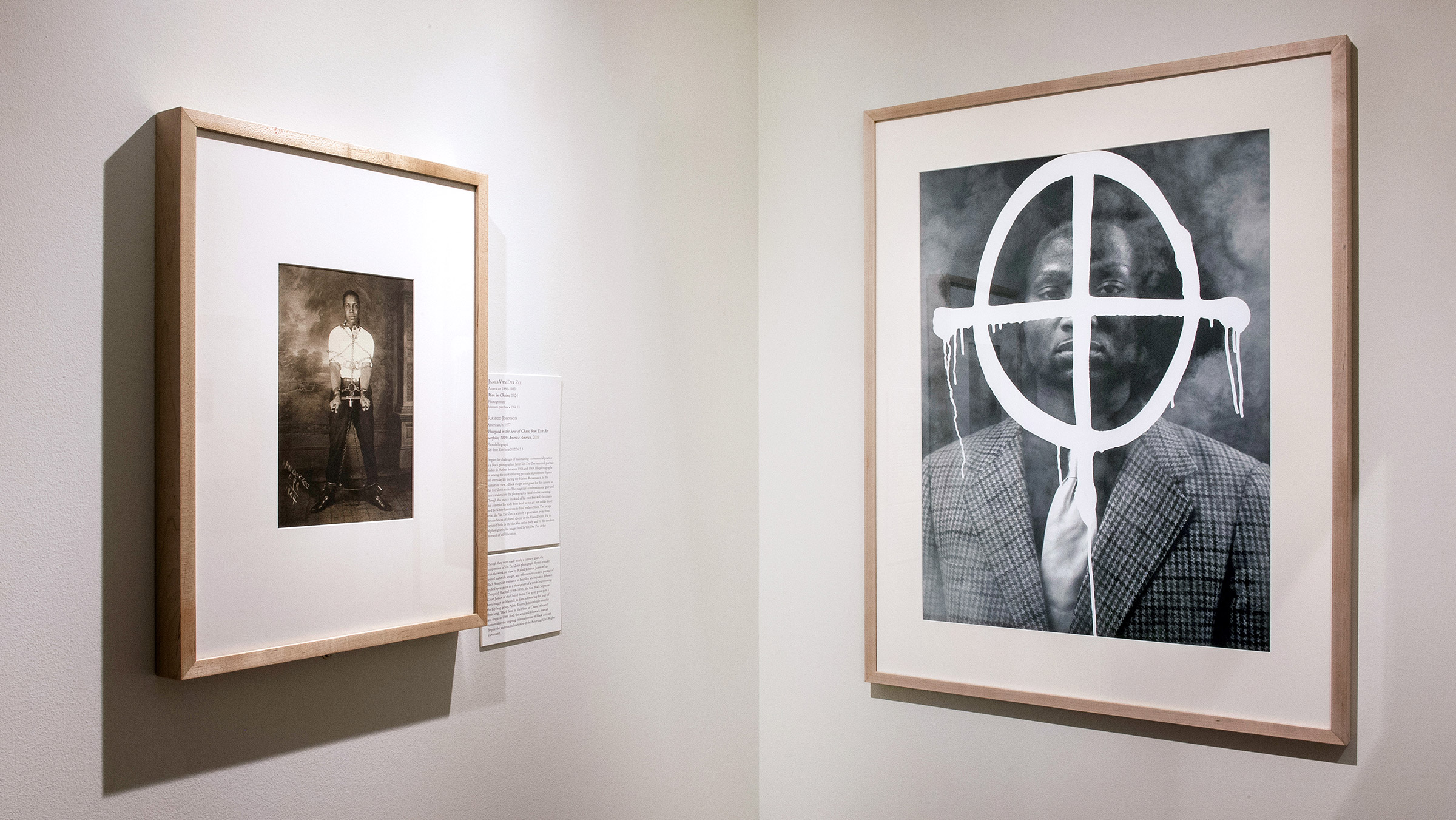

Photo: FLLAC, Purchase, Advisory Council for Photography, 2011.20Spanning nearly two centuries, the images in the exhibition feature works from the mid-nineteenth century through today. Photography was instrumental in the abolitionist movement, making Black subjects newly visible during Reconstruction. Images from this period attest to the use of photography for the self-preservation and self-composition of Black Americans. Moving into the 20th century, the exhibition includes works by James Van Der Zee, whose photographs are among the most enduring portraits of prominent figures and everyday life during the Harlem Renaissance. Nearly a century later, photographer Rashid Johnson rhymes visually with Van Der Zee with his layered materials, images, and references that create a portrait of Black American resistance to brutality and injustice. Artists Carrie Mae Weems and Arnold Joseph Kemp are featured, with works that explore the representation of an absent self through text and inanimate objects that serve as surrogates for human subjects.

Rashid Johnson, Thurgood in the hour of Chaos, from Exit Art portfolio, 2009: America America, 2009

Photo: FLLAC, Gift from Exit Art, 2012.26.2.3Other artists represented in the exhibition include Fred Wilson and Mickalene Thomas, whose work appropriates aspects of the White-dominated art historical canon to evoke the empowerment of Black subjects, and Jamaican-American artist Nari Ward, who frequently mines his own background as an immigrant to the United States to examine racial and economic disparity by combining found objects.

“I wanted to illuminate how and why Black artists have deliberately chosen photography as a tool to combat erasure and violence,” says Brier. “The ongoing struggle to make Black experiences more visible connects some of the earliest photography to important work made by Black artists today.”

All of the works in the exhibition are from the Loeb’s collection and reflect the museum’s efforts over the last decade to represent more artists of color through acquisitions and exhibitions.

“Visible Bodies: Representing Blackness” will remain on view through Black History Month at the Hoene Hoy Photography Gallery of the Loeb Art Center, closing March 7. The Loeb is open to the public Saturdays 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. and Sundays 1:00–5:00 p.m., with public entry through the sculpture garden on Raymond Avenue. The exhibition also may be viewed online.